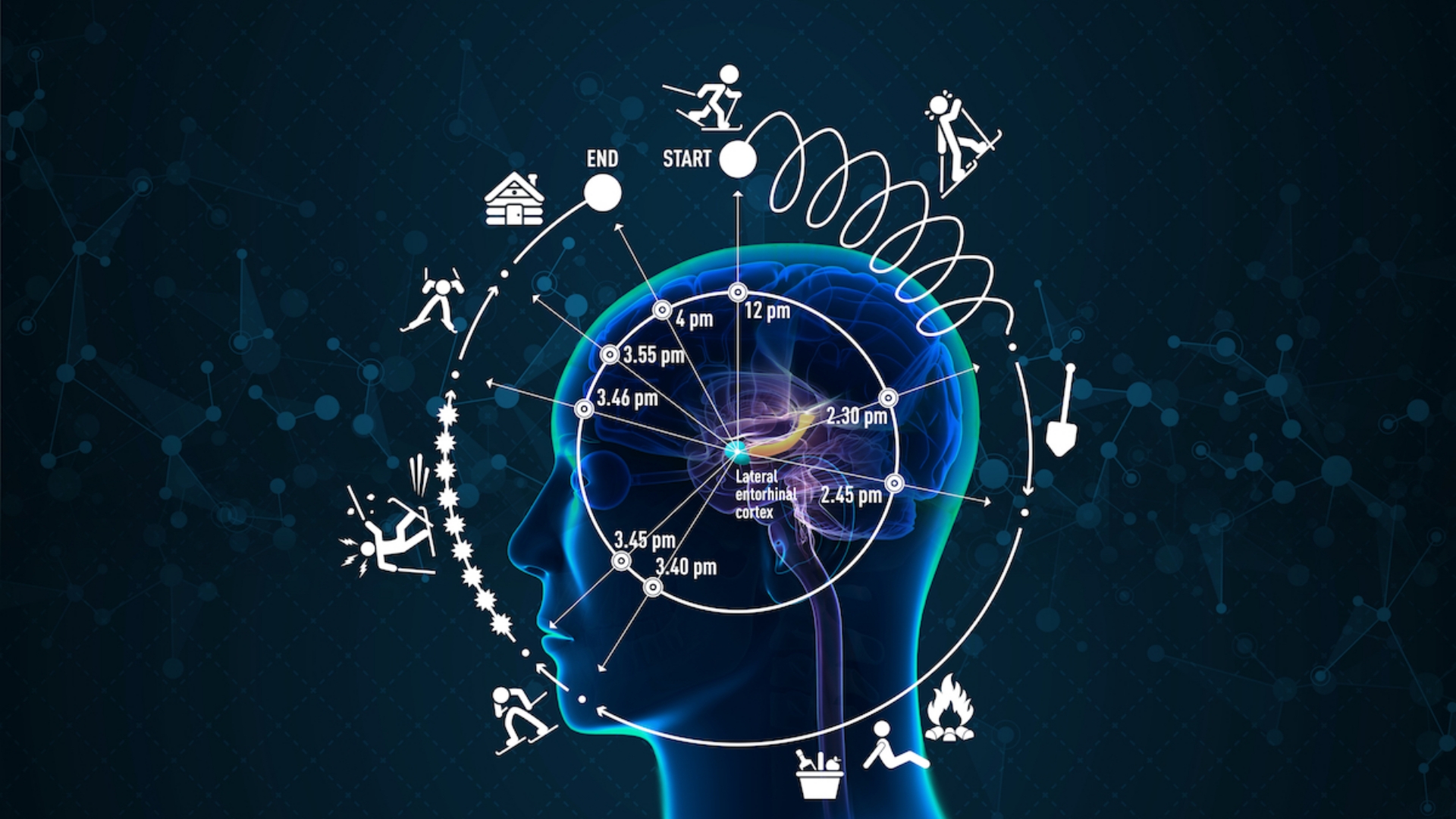

According to a study, the brain perceives time through activities rather than hours.

According to a study by UNLV researchers, our brains' synchronization with electrical clocks is not innate; rather, it is dependent on the quantity of experiences we have. Contrary to the proverb that says time flies when you're having fun, the researchers discovered that increasing speed or output during an activity alters how our brains perceive time.

"We tell time in our own experience by things we do, things that happen to us," said James Hyman, a UNLV associate professor of psychology and the study's senior author. "When we're still and we're bored, time goes very slowly because we're not doing anything or nothing is happening. On the contrary, when a lot of events happen, each one of those activities is advancing our brains forward. And if this is how our brains objectively tell time, then the more that we do and the more that happens to us, the faster time goes."

Each time a repeating motion is performed, researchers have discovered that brain patterns are similar yet somewhat different. They examined activity in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) of rodents that had to respond to a stimulus 200 times with their noses. When the animals progressed from the start to the finish of a task, the researchers noticed observable changes in brain activity. Regardless of the animals' speeds, the patterns always went in the same direction. The duration of an activity has little bearing on the brain's patterns since the brain functions as a counter, registering feelings about time. To complete the objective, the cells cooperate and randomly align, tracking movements, intervals of time, and activities.

We spend a large portion of our lives in short bursts of time, from a few minutes to hours, and a UNLV study looked at how our brains work in these situations. This study is one of the first to look at behavioral time scales in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), a region of the brain linked to anxiety, addiction, PTSD, mood disorders, and most psychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases. Alzheimer's disease and other dementias also depend on ACC function.

According to the initial results, knowing how time perception relates to memory functions may help regular people deal with situations like breakups or school tasks. The ACC, emotion, and cognition were also found to be significantly correlated in the study, indicating that understanding the brain as a physical structure may aid in the regulation of subjective experiences.